GP Life is a study guide written by a GP Registrar in NSW. As such, the focus is largely on NSW and central Australian communities for the purpose of studying for the ACRRM CGT StAMPS exam. The below is not to be taken as medical advice or relied upon for the diagnosis or management of real-life patients.

Gallstones are cholesterol-based aggregations of bile product which develop in the gallbladder and are present in something like 6% of the population at any one time. The majority of gallstones are asymptomatic and found when doing abdo ultrasounds or CT scans for other reasons. Symptomatic disease usually starts as biliary colic and then progresses to a complicated form of gallstone disease. It is also possible, however, for a first presentation to be of a complicated form of gallstone disease.

The nomenclature and management of gallstone disease depends basically on two things: where the stone is, and whether it is causing an infection. The key complications to remember are: cholecystitis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis.

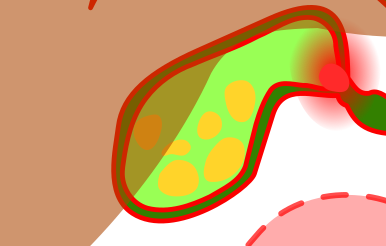

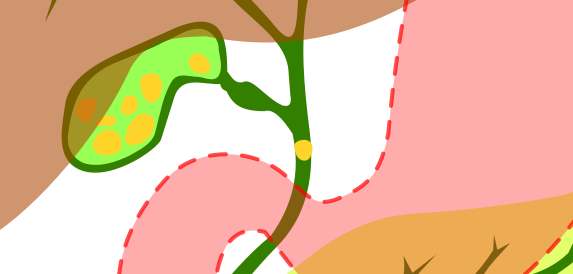

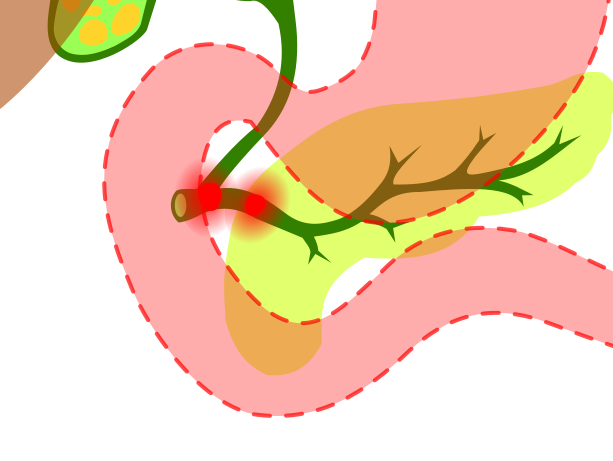

The below is a good overview of the anatomy of the biliary tree, complete with little gallstones to show you just where things can go bad:

Biliary Colic

Biliary colic describes the typical pain of symptomatic gallstones, caused by gallstones being compressed against the outlet of the gallbladder. The pain is most often present after eating (particularly fatty meals), and presents as constant, often severe RUQ or epigastric pain in episodes lasting 20 minutes to 4 hours usually. There may be associated nausea and vomiting or sweating.

The initial workup for patients presenting with typical symptoms in StAMPSville should include an FBC, LFTs (incl. bilirubin), and lipase, as well as an abdominal ultrasound. Conveniently, this can all be done locally.

Biliary sludge (fancy people call it “microlithiasis”, apparently) can cause symptoms of biliary colic to present, and can also cause pancreatitis and cholangitis.

Differentials to consider include GORD, peptic ulcers, Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction, and any of the complications of gallstone disease. Differentiating uncomplicated biliary colic from more severe forms of gallstone disease is an important skill for the general practitioner. Features raising concern for complicated disease include:

- History: Very severe pain, persisting >6 hours, atypical features.

- Examination: Fever, tachycardia, looking systemically unwell, guarding/peritoneal signs.

- Bloods: Leukocytosis, elevated bilirubin, elevated lipase, more than mildly deranged LFTs.

Acute pain management is complicated by the severity of the pain in a lot of cases. In the ED, ketorolac is reasonable. Oral NSAIDs are useful, with a 2012 meta-analysis showing there is no difference between NSAIDs and opioids in this setting, and halve the rate of complications of gallbladder disease (presumably via their anti-inflammatory effect).

Patients with symptomatic gallstone disease should be referred to a general surgeon for cholecystectomy due to their risk of recurrent symptoms and complicated gallstone disease. The risk of a complication is about 3% per year. Complications of cholecystectomy for the GP to be aware of is around changes in the way fatty meals are absorbed leading to diarrhoea, which often improves over a few months.

The below are the complications of gallstone disease. These would most likely emerge as an emergency station or as a question 3 in an initial office management station. Remember to focus on the initial A to E assessment and resuscitative management of shocked patients.

(Calculous) Cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis can be calculous or acalculous. Gallstones cause more than 90% of cases. In these cases, a gallstone obstructs the gallbladder neck, increasing pressure in the gallbladder, causing decreased blood flow to the gallbladder wall, leading to oedema and inflammation. In two thirds of cases, there will be a secondary bacterial infection.

These patients present with RUQ pain which persists more than 6 hours, as well as feeling systemically unwell and usually having nausea and vomiting. They may have Murphy’s sign (pain on inspiration preventing full inspiration while palpating the right subcostal area); this is sensitive and specific but not so much in elderly people. The triad for cholecystitis is:

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Fever

- Leukocytosis

Of course in STAMPSville we will not have a white cell count. In septic patients the lactate may be significantly elevated but this is not necessarily so and patients who have fevers and are at risk of cholecystitis should be discussed with surgeons.

POCUS may reveal a thickened gallbladder wall (>3 mm) or pericholecystic fluid. If the StAMPSville sonographer is present and willing to come into ED, this would be a good way to demonstrate the validity of your diagnosis while instituting other therapies. In a bigger centre, either ultrasound or CT could be used, with the preference normally being ultrasound.

These patients need antibiotics and urgent cholecystectomy. Delaying surgical treatment can lead to gangrenous cholecystitis or gallbladder perforation. The antibiotics currently recommended are ampicillin 2 g QID and gentamicin. If the patient can’t have gent, give IV Augmentin 1/0.2 g TDS instead. (Metronidazole is added for acalculous cholecystitis).

Choledocholithiasis

This just mean that a gallstone has progressed from the gallbladder neck into the common bile duct. 10% of patients with symptomatic gallstones have choledocholithiasis. There is usually abdominal pain.

At this stage in disease, patients will usually have an elevated bilirubin, GGT, and ALP. However, uncomplicated choledocholithiasis should not lead to a raise in inflammatory markers or lipase. The complications of choledocholithiasis are cholangitis and gallstone pancreatitis. ERCP is indicated.

Cholangitis

Acute cholangitis is an infection of the biliary tree secondary to choledocholithiasis. It is less commonly secondary to malignancy, or as a complication of ERCP. These patients are sick and there is a high risk of gram negative bacteraemia. Patients also need to be covered for anaerobes. Charcot’s triad is a helpful guide to diagnosis:

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Fever

- Jaundice

This is extended to Reynolds’ pentad if there is also hypotension or mental state changes.

Again, we will not have LFTs, bilirubin, or inflammatory markers at a sufficiently quick pace in STAMPSville. A POCUS wizard or the sonographer if around may be able to see CBD dilatation or stones.

Management priorities include resuscitating the patient: take off some blood cultures and give some crystalloid as well as antibiotics. Treatment is with gentamicin and ampicillin 2g QID, plus metronidazole for patients with chronic biliary obstruction (in practice, I’ve always seen metronidazole given). If you can’t give gent, cef and met or piptaz are the options. Don’t forget some good strong pain relief as well.

Most patients with mild-moderate cholangitis respond well initially to antibiotic therapy but still need ERCP in 24-48 hours. Severe cases need biliary decompression within 24 hours. So speaking to surgeons and retrieval is a must. Remember the regional hospital may not have ERCP capability depending on the day of the week, staff availability, and the alignment of Mars relative to the orbit of Jupiter.

Gallstone Pancreatitis

Gallstone pancreatitis arises from obstruction of the pancreatic duct or ampulla. This causes bile to reflux into the pancreas, causing it to eat itself. Yummy!

Again, diagnosis in the acute setting in StAMPSville would be extremely difficult unless you got lucky with the timing of couriered blood samples (if so, send FBC, EUC, LFT, lipase, CRP, blood glucose). Ultrasound may again be useful, but here I doubt even the most stubborn POCUS nerds could be confident in a diagnosis. CXR may be useful for pleural effusion or features of APO or ARDS (third spacing from the badness). AXR may show localised ileus. In general a patient with jaundice and sudden-onset severe epigastric pain should be treated aggressively and transferred early regardless of whether the diagnosis turns out to be cholangitis or pancreatitis.

Standard management of pancreatitis applies. Call the GPA; resuscitation may involve intubation (with a protective ventilation strategy). Aggressive fluids +/- pressors if hypotensive. Analgesia is also important to reduce oxygen consumption.

Consider antibiotics (take cultures if you’re going to give these). If a patient has a fever it would be tough to distinguish cholangitis without a lipase, so antibiotics would be reasonable in StAMPSville.

Ensure patients are getting good pain control and good intravenous rehydration: a 1L bolus then 250 mL/hr is a reasonable place to start. In the critical care setting this would be titrated to urine output with careful monitoring for features of overload. Manage other symptoms like nausea/vomiting. Early enteral nutrition is favoured for these patients (“pancreatic rest” doesn’t seem to really work), but in the timeframes we will be dealing with them in StAMPSville they won’t be thinking about eating.

Acalculous Cholecystitis

Acalculous cholecystitis usually occurs on a background of other serious disease: AML, AIDS (and other causes of immunosuppression; think opportunistic infections), severe burns, and cancer. This usually occurs in the setting of hospitalisation or intensive care admission. Management is largely the same except for the addition of broader-spectrum antibiotic coverage (eTG says just add metronidazole, but knowing our intensive care colleagues I wouldn’t be surprised if most of these guys end up on meropenem).

Example Question

Sandra is a 52-year-old woman who is presenting to your clinic complaining of episodic right upper quadrant pain over the past month. This seems to mostly occur after eating. She is taking rosuvastatin 5 mg nocte and semaglutide 1 mg weekly (for obesity), but reports she is usually quite well.

- Outline your initial assessment and management of this patient. (4 mins)

- An ultrasound confirms gallstones are present. Sandra presents to your surgery a few weeks later. She is frustrated by the ongoing episodes of abdominal pain despite initial management attempts. She hears that it can take up to a year for surgery to have her gallbladder out. How would you counsel Sandra today? (2 mins)

- Sandra presents to ED late at night with severe abdominal pain, fevers, and jaundice. She looks unwell, with a heart rate of 120 bpm and a blood pressure of 95/60 mmHg. How would you manage Sandra? (4 mins)

Leave a Reply