Disclaimer: While I have passed ACRRM CGT StAMPS and have spoken with various characters behind the scenes, I am not an examiner for StAMPS or affiliated with ACRRM in any official capacity. This information is based on publicly-available information and my experiences with the exam and with the College and, as such, is not particularly well-referenced. I sat in July 2024. Information here is current as of the time of writing, March 2025.

StAMPS is often seen as “the big one” for ACRRM trainees. While ACRRM is at pains to say it’s not a Fellowship exam per se, it’s functionally the main barrier that determines that your skills are at the expected level of a rural and remote medicine specialist. StAMPS has a higher fail rate than MCQ or CBD, and therefore requires a lot more preparation. It also produces a lot of anxiety, some needed, some unnecessary. Here I hope to dispel some myths to make your StAMPS preparation journey a little easier.

First of all, I think it’s important to say that StAMPS is a rigorous and well-designed assessment. The design process for the exam is shockingly in-depth with multiple stages of development and quality assurance. The scenarios discussed are very realistic to rural generalist practice and examined to a fair standard. Results are statistically reviewed for anomalies and there is a system in place to ensure that nobody fails who wasn’t “meant” to fail.

Without meaning to blow smoke too far up the college’s proverbial, I can confidently tell you that I walked out of the StAMPS exam feeling like if I didn’t pass, I wasn’t ready to be a FACRRM. At the end of the day, we want our fellowship to mean something; to signify that we know what we’re talking about when it comes to all aspects of rural medical practice independent of any other qualifications.

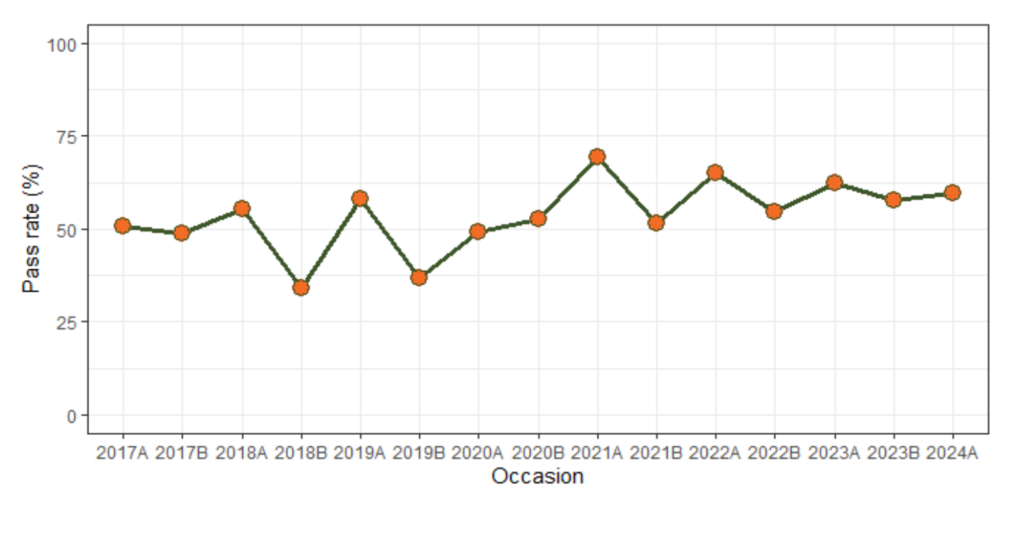

All that said, yes, the overall pass rate can be quite daunting at first glance, hovering somewhere between 50-60%:

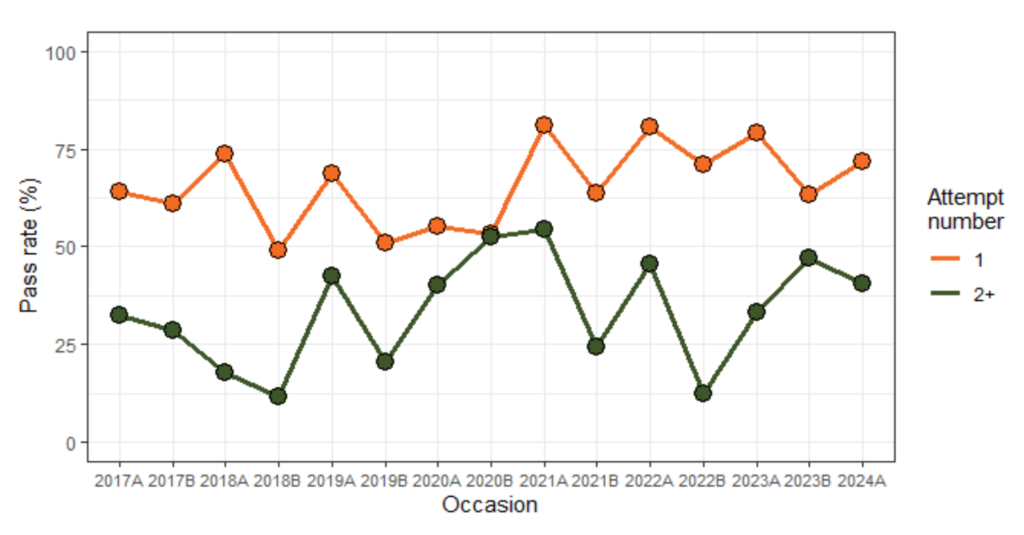

And it’s much worse for those re-sitting the exam:

This is quite striking. Check out 2022B: something like 75% of first-time candidates passed while only 13% of re-sitters got through.

Until recently there was no number of maximum attempts, and at $3595 per attempt, the rumour was that if you fail enough times ACRRM actually will erect a gilded statue in your honour. However ACRRM are now introducing a cap on number of attempts (four) which brings them in line with most other colleges.

A couple of things to say about these stats. The first is that ACRRM know that your likelihood of passing is correlated with your score on your selection interview (as per a presentation at RMA ’22). The second is that International Medical Graduates as a cohort have a considerably lower pass rate than local graduates, so this skews the pass rate down. This may be reassuring or disheartening depending on who you are. But in any event, the exam is hard, which means you need to be prepared.

Okay fine, but what is the exam?

StAMPS is a viva-style exam that will be familiar to many; for UNSW grads, it’s kind of a similar structure to the fifth year Biomed Viva barriers. The exam is conducted using an online, web-based system. In my experience this system worked very well, but there were many reports of substantial IT problems during the November 2024 sitting. During this exam you will cycle through eight stations and answer questions for a series of examiners. The whole exam lasts about 3 hours.

Each station consists of a stem and 3 questions. You have ten minutes to read the stem and prepare (it’s actually only 5 minutes reading time with an extra 5 minutes per station allocated to “fixing IT issues”), and then ten minutes to answer questions. You do not get to read the questions in advance. The questions are evenly-weighted across the ten minute station, so you have about 3 minutes and 20 seconds per question. The examiner should move you along if you’re stretching the time, but in reality practice is inconsistent.

The cases are designed to cover as many domains as possible within the rural generalist curriculum. As a result, some patterns emerge. Of the 8 stations, there are usually 1-2 emergencies (if there are two, one will probably be a trauma or multi-casualty event), 1 paeds case, 1 women’s health case, 1 mental health case, and 1 remote/tropical medicine-themed case (Q fever/typhus/leptospirosis etc.). There will also likely be one question about population health at some point, as well as a question that places you outside the scope of usual rural generalist practice in order to prompt you to appropriately involve a specialist (think stuff like Huntington’s disease and Kleinfelter syndrome).

Knowing this helps because it means there are certain “scripts” that you can pre-learn to cognitively offload a bit and make your life easier. For example, as we will discuss later, it’s important to have a script for a normal delivery, ALS, neonatal resuscitation, etc. That way when these things come up (which they invariably do), your mouth can do the talking and all your brain needs to actively do is adapt it to the case.

The Questions

Each station consists of three questions, all of which are roughly equally weighted in terms of time (so 3 minutes and 20 seconds each). They tend to (often but not always) follow a predictable pattern:

- The introduction: for most stations, this will be asking you to form a differential and do an initial assessment, however it can also include some preparation. For example, you may be asked how you would prepare to receive a trauma or a multi-casualty situation after a BAT call. In general though, the structure of this question will be to highlight either a list of differential diagnoses or an issues list, and then discuss your (focused) assessment, including history, examination, and pertinent investigations.

- Initial management: the second question can be quite varied. It often relates to management of the problem which you diagnosed in question 1. Often there is new information in this question which is used to guide your management plan. This is because a huge part of what this exam seeks to test is what the College calls “flexibility of thinking”. That is, how quickly can you pivot from thinking about managing an inpatient on the ward to managing a resuscitation?

- The Twist: This question again seeks to test your ability to adapt to a changing environment. The third question almost inevitably presents a particular conundrum or takes the case in an unexpected direction. For example, an ethical dilemma may be introduced (often having previously been hinted at), or a population health concern, or a new concern which needs to be addressed in the general practice setting.

We will go through some examples later after we lay some more groundwork.

What is StAMPSville?

StAMPSVille is the fictional town that serves as the setting for most of the StAMPS stations. The StAMPSville profile lays out the demographics of the town and the resources which are available (make sure you’re looking at the CGT StAMPS community profile and not one for an AST; particularly EM AST StAMPSville is a very different environment). CGT StAMPSville is a central Australian community with 4000 people and a considerable number in the surrounding district. There is a small rural hospital, an aged care facility, and two Aboriginal communities to which your team does outreach.

You do have to be careful because there is also a remote Aboriginal community that some stations can take place in, which has considerably fewer resources. Here you’ll only really have a remote area nurse and a fingerpick HbA1c.

Everyone says that StAMPSville was modelled on their town, but in reality there are dozens of cognate towns across the country. A great example would be Tennant Creek. Adjusting to the concept of StAMPSville can hard for people whose rural time has been in MMM4 sites with a few more toys (and staff) to play with. But there’s also a trap for people who are working in a similar location in that the resources you have available to you will be slightly different. I found StAMPSville to be quite similar to my main (MMM5) training location, but StAMPSville had far more resources (blood, allied health, nurses etc.). It’s easy to forget to involve the physio when you haven’t had a physio in your personal StAMPSville for years.

It is critically important to give an answer that’s tailored to the StAMPSville environment. One of the big flags that the examiners are looking for is giving an answer that is relevant to StAMPSville and not to your own context and certainly not to an urban or regional setting. Again, this is because we want FACRRMs to be able to practice in any kind of environment in an independent manner. It doesn’t matter what you would do in your town, it matters how you play it out in StAMPSville with the resources you have available to you.

So know StAMPSville. Pin the community profile to your toilet door and start memorising what’s there. You do get to have a copy for the exam but you do not want to spend any time referring to it. If you’re in a MMM5/6 site already I found it helpful to visualise myself in my own StAMPSville ED just to help really put me in the right headspace when I’m starting to work on a case.

NB: In the StAMPS exam, you are the senior medical officer. You are not the registrar, because you’re trying to show examiners that you know how to do your job at a senior level. Make sure embodying the leadership and team management skills expected of a FACRRM is part of your practice.

What Should I do to Prepare?

In order to even be allowed to sit StAMPS, you need to tick two boxes: to have passed MCQs and to have completed a “formal preparation activity.” Clearly the big hurdle here is the MCQs, and once you’ve passed that you can be fairly sure that you have the knowledge needed to pass the exam. The rest is about technique and showing examiners that you are functioning at the level of a capable rural generalist.

How long to prepare is really up to your needs, but I would suggest at least six months. I started by watching a more senior registrar prepare for their exams and helping out with some practice which was ultimately about 18 months before I sat. Naturally, your preparation will ramp up steadily as you approach the exam.

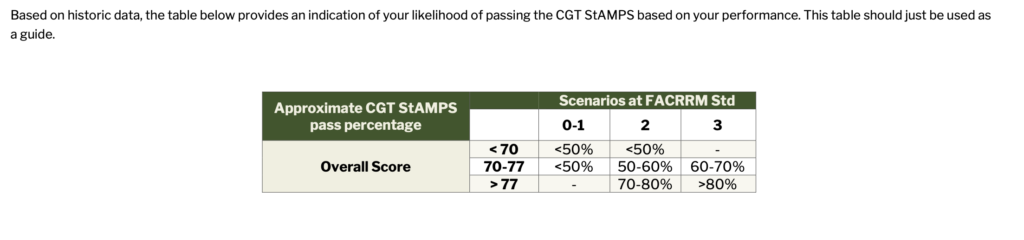

The college sets up two valuable resources for you which would be silly to ignore. The first is “Mock StAMPS”, which is what it says on the tin: a session which is also run online via the same software as the exam, to demonstrate how the exam runs and the expected standard. This happens a few months out from the exam which is great for expectation-setting and even testing practicalities like IT setups. You get some model answers, advice from examiners, and even a matrix which shows you based on your performance and historical data whether you are likely to pass the real exam.

However, this isn’t completely predictive and I do know a couple of people who “failed” mock StAMPS and went on to do quite well in the real thing (and vice versa). “Failing” mock StAMPS, however, should prompt a discussion with your medical educator about your path forward.

The second preparation activity is the CGT StAMPS study groups. Here you are assigned to a group with five-ish other registrars and a facilitator who is a CGT StAMPS examiner. They will walk you through some practice cases and provide advice and opportunities to practice your exam technique. This happens over 8 or so sessions. Shockingly, some people sign up for this and then don’t turn up to the sessions. I would highly recommend doing everything you can to attend these sessions. Your attendance (or not) is also noted by the college (presumably so that fingers can be wagged in the event of you failing the exam if you didn’t show up for the prep group).

In addition to these formal preparation activities, most registrars will participate in informal study groups which are prepared amongst your cohort. There are usually some WhatsApp or Facebook groups you can join if there are no other ACRRM registrars at your site. Otherwise some more forceful networking by calling around to some nearby training practices to try to get in touch with other registrars might be in order. My prep group had five people meeting online once a week for a couple of hours to run through cases starting a few months out from the exam.

There is a Reg Com “book” (pdf) of practice cases floating around. This is written by registrars but the quality of the questions varies wildly. It’s a great resource in terms of the topics it covers but some questions don’t fit the format of the actual exam. As this site progresses I’m hoping to have more fleshed out versions of most of these questions. The key, however, will be to practice in a group. You aren’t going to know if you have a bad habit or make a lot of errors in your presentation if you aren’t getting feedback from others. This also means being good at giving specific, constructive feedback yourself. The “shit sandwich” model is highly useful here.

Finally, there’s individual preparation. For this I would recommend two strategies. The first is to actively identify weak areas in your practice and work on these. You can use the rural generalist curriculum for reference, however I’d look mainly at the curriculum areas rather than the specific conditions listed in the curriculum; there are some glaring omissions in the rural generalist curriculum which are clearly in our scope of practice, and questions are commonly asked across the ACRRM exams which fall outside the curriculum.

The other strategy is to develop some “scripts” for various common scenarios that you might need to talk through. This allows you to (mostly) turn your brain off and just talk when the question arises. Some key scripts which I think are important to develop are:

- Advanced life support

- Neonatal resuscitation

- Primary survey (for trauma)

- A-E assessment/management for a critically unwell (Cat 1/2) patient

- Preparation of the ED for an unwell patient or multiple casualties

- Preparation of a patient for retrieval

- Initial assessment of an unwell infant

- Management of normal delivery

- Shoulder dystocia (for example, with HELPERR)

- Breaking bad news

I have not included example scripts because I think it’s important that these are natural to your style of speaking. Just keep timing in mind, and build in enough flexibility that you can comfortably only include part of these scripts.

Note for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Trainees: If you haven’t already, please join IGPTN. Membership is free. There are 6-monthly education workshops as well as online study groups which are available to you. It’s also a great opportunity to get together with mob and know you’re not doing it alone, as well as getting inspired by people who’ve walked the path before you.

How do they Mark the Exam?

The examiners score you on a scale from zero to seven. This is so they cannot sit on the fence between a pass and a fail.

- A score of 0-1 represents a candidate who is unsafe or inappropriate.

- A score of 2-3 represents a candidate who may be a good registrar but isn’t yet at the standard expected of a FACRRM.*

- 4-5 represents a safe and appropriate rural generalist ready for independent practice

- 6-7 represents an exceptional candidate.

*: ACRRM love saying this, but I haven’t been able to pin anyone down on an explicit definition delineating who is a “good registrar” and who is at FACRRM standard. It appears to be largely vibes-based, which is fine but unhelpful.

In addition to getting scored from 0-7 for each question, you also get scored on 3 extra domains: systematic approach and problem definition, communication and professionalism, and flexibility to changing context (there’s that phrase again). In addition to these, you get a global rating as to whether you performed “at FACRRM standard” for that station.

So in total you have 6×7 = 42 points up for grabs per station, meaning the exam is out of 336 total points. The pass mark is a straight number based on some statistics they cook up, but generally 195 +/- a couple of points (about 58%).

A “review zone” is set from ten points below the pass mark (so, around 185). Candidates who fall into the “review zone” automatically have the videos of their responses formally reviewed by a separate set of examiners in order to ensure that marking has been fair.

There is clearly a level of reflexivity built into the system and, as such, it seems hard to imagine how an appeal would ever be successful (though I’d be interested to hear about this if it has happened). The exam is designed such that those who could ever pass on review are reviewed anyway. It’s also worth keeping in mind that appeals are costly process.

Some Key Advice

Of course, as with everything relating to rural generalist training, everyone’s journey is different. However I think there are some key elements which I’ve noticed seem to trip people up or reliably predict success. Again, I’m not an examiner, just someone who’s seen a lot of colleagues go through this, so take it all with a grain of salt. But without going into too much detail, you’ll have to trust me that many of these opinions are shared widely.

Pitfalls:

- Not having enough (real) rural experience: I’ll never forget reading a tweet from an ortho reg who was very humbled by his “rural” placement… in Cairns. We all have a story of someone who wants to be a “rural generalist” in a town way bigger than a bona fide rural generalist has any business operating in. Make sure you’ve worked in some MMM4+ environments before you sit the exam, or you will seriously struggle. Ideally, you will be operating as a rural generalist, covering GP, inpatient, ED, and nursing home settings. This is the best form of preparation and it really shows when candidates have done the work before.

- Not having enough general practice experience: ultimately, the majority of this exam takes place in a GP office. You could probably pass it if you are really good at primary care and can bumble your way through a resuscitation. It’s unfortunately quite common for ACRRM registrars to be fairly exclusively focused on emergency medicine. You will see these people in your study groups as those who suggest epidural abscess or a AAA rupture before non-specific low back pain in a patient presenting with a sore back. Don’t be that guy, it’s cringe.

- Not having a sufficiently varied casemix: if you are working rurally and doing enough GP work but all you see is kids and pregnant women, you will still struggle with this exam. You really need to be seeing a bit of everything in order to feel confident with this exam, because it’s explicitly designed to assess your performance across all domains of rural practice.

- Communication skills: while it’s only explicitly marked in one of the 6 categories for each station, your communication skills are critical for getting enough dense information across to the examiners to get through. You don’t have time to speak slowly or repeat yourself. You cannot risk not being understood. You need to be clear and concise and confident in order to do well in this exam. This comes naturally for some and not for others. For those who struggle with this, either due to training or self-confidence issues or a language barrier, you must work on this. And the great part is it will make you a better doctor and a better colleague, too.

- Trying to listen to all the advice you get from everyone: throughout your StAMPS preparation, you will (hopefully!) come across a lot of helpful people who have examined StAMPS or passed StAMPS, and all of them will have (often conflicting) advice on how to best get through this exam. Everyone is also very confident that their way is the definitive way to pass StAMPS. This will get annoying and confusing. There are, in truth, a number of ways to structure your responses to get through, and you just have to choose a way that makes sense in your head and that allows you to give a fluent, convincing answer. Do not change your approach last-minute on the advice of one person, unless there’s something really wrong.

Tips:

- Don’t let a question go past without making it clear that you know you’re in StAMPSville and are understanding of the rural and remote context. A tidy way to do this would be to make note of any time you’re calling on a resource not available in StAMPSville: “I’m not able to rule out a brain tumour in this patient without imaging, which will need to take place in the regional centre. I’d explain to the patient the importance of getting this study and identify any barriers such as transport or other commitments and work with the patient to address these.”

- Don’t waste time repeating information in the stem in the first question. You don’t need to say “this is a 60-year-old patient from StAMPSville presenting with new headaches and diplopia, with progressive symptoms over 2 months.” Just jump straight into: “I’m most worried about a space-occupying lesion for this patient, with potential differentials including…”

- You may be interrupted, prompted, or moved along. This can be quite jarring but it’s important to recognise that this is because you’re not doing anything to improve your answer, so you need to change your approach. The most frustrating form of this is at the end of a response: “is there anything else you’d do?” This is a mind-reading game but do your best to pad things out without completely bullshitting.

- You don’t need to be completely exhaustive with your history and examination findings. As the supervisor of my prep group said: “you’re examining at the level of a senior doctor, not a medical student. In reality you don’t have time to do a 45 minute history and complete neuro exam on every patient. Tell us what is pertinent and why, and link it back to the question.”

- You are allowed to explain that you’d call on resources to help you, but be specific: “I’d refer to eTG for the dosing of benzylpenicillin” rather than “I’d double-check the dosing”. Similarly, you can absolutely say that you’d call a specialist, particularly if that’s what you would do in real life, and some stations will expect you to do this. You don’t need to be an expert on managing copper toxicity, just to know who to call to get the patient the help they need.

- Similarly, be specific in your interventions. “I would start by giving resuscitation fluids” wouldn’t be looked on as favourably as “I would ensure there are two at least 18G cannulas sited and initiated resus fluids with 1L of normal saline given over 20 minutes.”

- Relate key points back to the context of StAMPSville but also that of the patient! For example, a patient who lives remotely on a farm 100 km out of town may have different needs to a patient who lives in StAMPSville itself.

- Think about the practical stuff: try making phone calls to line up appointments to minimise travel for your patients, and recognise the challenges of life in a rural community. That sort of thing just makes it clear who has actually worked in these kinds of environments.

- ACRRM want you to pass — at the end of the day we all want more working rural generalists — but they also have an important role in making sure Fellowship of the College is a meaningful qualification. Try to keep that in mind when things get frustrating.

My Approach

Enough preamble! Here’s how I tackled the StAMPS exam, by way of an example question. As with any question on this site, I have totally made these up and they are not at all based on any previous exam question (because this would obviously be academic misconduct and probably some sort of copyright fuckery):

Your next patient in the StAMPSville clinic is Steve Stevenson, a 63-year-old gentleman who presents to you with right foot pain and paresthesias which have progressed over the last 2 weeks. His wife told him to come in because he has a sore on his foot.

He has known type 2 diabetes, and currently takes metformin 500 mg BD and empagliflozin 10 mg mane. He is an active smoker of 10 cigarettes a day, and works locally as a mechanic.

During the prep time for each station, I would divide an A4 sheet of paper into 9 segments. This is a common way of preparing that most people will do some sort of variation on. Please see mine for your consideration below, but do adapt it to what you need.

| [S] | Ix | Mx |

| Hx | Ddx | Scratchpad |

| Ex | Issues | P R I D E |

While most of this is fairly self-explanatory, there are a couple of things that need a bit of unpacking. Top left is a quick summary of the scenario, because you won’t really have access to this once you start the scenario. Hx is the key history points you want to know, as for Ex and Ix. Ddx is your differentials, which I’ve put in the centre because it will be basically the first thing you talk about. A good piece of advice I received is that what you talk about when discussing your key history and examination points should be linked to specific differentials (but you don’t need to be explicit about this). Issues will discuss things that are relevant to your general practice management of the patient.

Investigations should be divided into stuff you can do in StAMPSville and stuff you need to send away, and by bedside tests (UA, urine BHCG, ECG), bloods, and imaging. Remember you have X-ray every day and ultrasound 3 days a week in StAMPSville, as well as POCT bloods. Everything else gets sent away.

Management is best thought about with immediate, medium term, and long-term management. I leave a spot blank to scribble down details for questions 2 and 3 (in reality this happens very quickly so you don’t need much space).

PRIDE is a crude and cringe mnemonic I have devised for common considerations that I might otherwise forget to address. It stands for:

- Population Health: some questions obviously hint at population health considerations. They might ask you about suicide prevention activities in your community, or working with the public health unit to manage a scabies outbreak. If there is a relevant issue, I jot it down to prime my thinking for it later.

- Rural/Remote Context: What about StAMPSville is going to play into this case? Does the patient live remotely? Are they likely to need intensive specialist follow-up?

- Indigenous: is the patient Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (or less commonly, another CALD background which needs consideration, for example a backpacker or migrant worker)? How is this going to play into my answer?

- Driving: Do I need to think about whether I need to instruct the patient not to drive or report a condition to the driving authority?

- Ethics: does the stem prompt an obvious ethical conundrum? Confidentiality? An impaired colleague? Mandatory reporting? Again, I’ll jot it down here to prompt my brain a little.

So for Steven, my grid would look something like this:

| Steven 63M [R] foot pain + paresthesias T2DM on metformin + SGLT2i | FBC, EUC, CRP, HbA1c, uACR XR ? bony involvement | ? Stability/need for hospital management Possible need for debridement |

| Review file for recent bloods Preceding trauma Relation to activity Previous episodes Fevers/systemic sx | Diabetic foot infection Osteomyelitis Venous or arterial ulcer MSK injury | |

| Vitals, features of sepsis? Interdigital — ulcers? Contamination? Vascular changes | Disposition today T2DM control Smoking cessation Other health screening: bowel, htn, alcohol use. | Pop: ?? R: possible transfer I: Not stated D: ? commercial, will need assessment E: ?? |

Clearly, for an emergency case, things work a little differently. We will discuss one of these below.

For this case, we could pretty easily predict that question 1 will look something like:

“What is your approach to this initial consult?”

This is code for: What do you think is going on here? How would you assess this patient (history/exam/investigations)? What are your aims of the initial consult today?

I like to run through these in a standard order starting with the differentials, which is the format that most markers will be expecting:

- Aims of the consult (very briefly): My main concern in today’s consult is determining a disposition for Steven. If he has a significant diabetic foot infection he may well need admission to StAMPSville hospital and if there are features of sepsis we may need to move him to ED for resuscitation and initial management.”

- Differential diagnosis: “Assuming he is stable, my main differentials would be a diabetic foot infection, osteomyelitis, Charcot foot, a venous or arterial ulcer, or a musculoskeletal injury. Less likely possibilities would include DVT or B12 deficiency.”

- History: “I would review Steven’s file to check if there is a recent A1c on file for him prior to the consult and to review his medications. Pertinent history would include asking about …. I would also ask about longer term diabetes issues, including A1c and renal function and monitoring activities, including last optometry and podiatry review. Cardiovascular risk factors would also be important to consider and I would be asking about today, including smoking status and history of hypertension.

- Exam: “I would take a full set of obs if my nurse hadn’t already, particularly ensuring that there’s no fever or hypotension. I would examine the lower limbs thoroughly for features of…”

- Investigations: You can divide these into bedside tests (eg ECG, ABI), bloods, and imaging. It’s also important to distinguish between what you can do locally and what you need to send away for. “Bloods would include an FBC, EUC, LFT, HbA1c/fasting glucose, CRP. If I had acute concerns I could do a POCT lactate locally. Imaging would depend on the examination findings but would start with an X-ray of the foot and likely arranging arterial dopplers for the next time the monographer is in town.”

- If you aren’t then stopped or moved along, you could start discussing initial management, however this requires you to make an assumption about the probable diagnosis.

Question 2 might then look something like this:

On review, Steve has an ulcer on his right heel. There is evidence of infection on examination. There is no fever or haemodynamic compromise. What are your next steps in managing this patient?

In response to this question, there are 3 key components to consider. The first is what your immediate management of this situation might be, the second is arranging follow-up and safety netting, and the third is the broader contextual factors that contributed to the original presentation.

- Immediate management: should include a reference to swabbing the wound and starting empiric antibiotics based on your guidelines of choice (eTG says oral Augmentin), analgesia, and community nursing follow-up for ongoing dressings.

- You would also consider speaking to the surgical registrar about this and potentially arranging some surgical clinic follow-up depending on the severity.

- Thinking about the management of his diabetes and using this acute illness as an opportunity to convince Steve to take his condition seriously and start working on his A1c control and all the “cycle of care” things (renal monitoring, eye checks, foot checks) would be important here.

Question 3 is the twist. This might take us in a new direction for the question or introduce new information (or sometimes even a new patient) that causes you to adapt and present something less rehearsed. For Steve, the predictable issue is driving:

Steve is treated and recovers from his acute illness. His wound is receiving ongoing dressings with community nursing. He comes to see you 3 weeks later as he holds a commercial license and is seeking medical review and clearance. Bloods you sent during your initial review are below. What pertinent issues would you discuss at today’s appointment?

[CURRENT] [6 months ago]

Hb 158 147 (120-160)

Plt 250 186 (150-400)

HbA1c 8.8% 8.6% (<5.5%)

eGFR 48 55 (>90)

AST 38 36 (<35)

ALT 46 42 (<40)

GGT 68 55 (<50)

CRP 55 (<5)Steve clearly hasn’t been taking care of himself! This is a common scenario encountered in clinical practice.

I would start by addressing the ongoing raised CRP, ensuring his stability and suitability for IV antibiotics, and talk about the length of course and other clinicians you may need to get involved (eg seeking ID phone advice).

Also make explicit note of his poor glycaemic control, presence of probably CKD based on prior bloods, and LFT derangement likely representing MAFLD. I’d start by saying I’d repeat the bloods (with a urine ACR) as his clinical infection resolves and further discuss CKD management at that review, including education on monitoring and the importance of risk factor control, and starting an ACEI/ARB.

In terms of the driving itself, an ideal answer would differentiate between a commercial license (which would require specialist review) and a private license, and discuss the key points in diabetes that can pose a risk in driving (hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, vision, altered sensation, comorbid risks like cardiovascular pathology).

This would also be a good opportunity to show you are a good, holistic GP by throwing in your preventive medicine stuff. For this patient, I would quickly mention:

- Discussion of smoking cessation.

- Alcohol consumption.

- Exercise.

- Weight management.

- Bowel cancer screening.

- Yearly flu vaccines, pneumococcal vaccine.

- That all of the above may take a number of visits and that a care plan would be an appropriate way to capture all these issues with some dedicated time with you and your practice nurse.

Depending how you are going for time, you could be asked to expand on the above, but if you get to that point you’re probably already smashing the station.

What About Emergency Cases?

Let’s try a trauma case, one of which pops up in most StAMPS sittings:

You are writing up notes from your last patient in StAMPSville ED when you get a call from the paramedics to tell you about an incoming multi-trauma.

There was a single-vehicle MVA rollover 30 km out of town. There were four occupants in the vehicle. Of these, one was deceased at the scene. The three passengers coming to StAMPSville are a 9-year-old boy with minor injuries, a 32-year-old woman with a head injury and decreased level of consciousness, and a 35-year-old man (the driver) with an increasing oxygen requirement complaining of left chest pain. They are coming lights-and-sirens and are 10 minutes away.

With a case like this, there are a few questions that can be asked of you. The most obvious is a variation on:

Describe how you would prepare your emergency department to receive these patients.

I would start this response by calling out that this is likely to outstrip the resources available to you in StAMPSville with two patients who are likely to be unstable, and while the child appears well currently, could also deteriorate fast. The presence of a fatality at the scene speaks to the intensity of the mechanism which increases the risk. A useful acronym is “PEDL”, which I’d write at the top left of my sheet:

- People: call in the GP anaesthetist, ACRRM registrar, and medical students if available for extra hands. Make sure you get the nursing staff around from the ward and call in extra people if available. Make sure the radiographer is available also. Staff should be divided into teams looking after the different patients and the med students can act as runners. Brief staff and prepare them to receive the patient.

- Equipment: Fully-stocked resuscitation trolley including bag-valve masks, airway adjuncts, oxygen masks and tubing, and cannulas. Know where the Oxylog/Hamilton is if required.

- Drugs: Analgesia, rescue drugs (adrenaline, metaraminol), sedation (ketamine/fentanyl/midazolam/propofol), IV fluids, confirm stock of blood.

- Location (where are they going when they arrive and after resuscitation): Clear out the rest of the department and assign someone to control the waiting room. Move any stable acute patients around to the ward. Call the state retrieval service and notify them if ambulance haven’t already.

On arrival, you opt to review the driver. He is tripodding with increased respiratory effort and is somewhat combative. Obs are SpO2 90%, BP 98/75, HR 120. How would you assess and manage this patient?

In the setting of trauma, I would start with a primary survey using the (c)ABCDE schema:

- (c)atastrophic haemorrhage (and C-spine): is there any obvious limb bleeding that needs an arterial tourniquet? Abdominal/chest injuries that need pressure? Does the C-spine need to be stabilised? (though consider the risks of immobilising in this patient who is already combative).

- Airway: are there any obvious features of airway injury or obvious tracheal deviation? Again, if he’s sitting up and maintaining on his own a hands-off approach might be reasonable.

- Breathing: watch his respiratory effort, check sats. Oxygen via Hudson mask or NRB depending. Listen to the chest. If there are features suggestive of tension at this point I would decompress the chest (needle to temporise then finger -> ICC).

- Circulation: BP monitoring + 3 lead ECG. 2 large-bore IVCs with bloods for POCT. Assess CRT and whether he’s looking shut down. Initial fluid bolus of 500 mL crystalloid if low BP or tachycardic or start transfusing O neg if there is apparent blood loss.

- Disability: pupil assessment, GCS, gross focal neurological deficit. Also consider whether there might be drugs involved given he’s the driver and consider at some point that you need to take a formal blood alcohol level.

- Exposure: check the abdomen for bruising, quick palpation, assess the hips with gentle compression. Note the positioning of a pelvic binder if one is applied (though this guy is sitting up so presumably not). Check for evidence of long bone fractures.

I’d then proceed to a chest + pelvis X-ray and then an eFAST (and talk about the different views and potential pathologies identifiable on those modalities).

You could also talk about analgesia, checking back in with the team to see how the other patients are going, and updating retrieval.

You are unable to appreciate any breath sounds on the right side of the chest, and there is no lung sliding on the right on bedside ultrasound. He remains tachycardic and hypotensive and sats are not improving despite 10L oxygen via non-rebreather. The patient smells strongly of alcohol and is increasingly combative. What are your next steps?

Certainly a nightmare scenario. I’d start out by calling out that there are two issues here: (1) that this is clinically compatible with a tension pneumothorax and is a life-threatening emergency, and (2) the patient will require sedation in order to be settled enough to tolerate a chest drain.

A key thing to mention here is, as in real life, you have a camera and the ability to dial in a critical care specialist to offload some of your decision-making here. Make sure you mention that you’d keep them in the loop especially if you aren’t confident with chest drains and sedation.

If the GPA has managed to stabilise his patient, his assistance will be critical here and I would assign him to manage the patient’s airway and sedation needs while I set up for a tube. Note that if the patient is deteriorating rapidly, I could temporise the situation with needle decompression at the 2nd intercostal space/mid-clavicular line, but the goal will be definitive decompression with a tube and underwater seal drain.

There are a number of options to sedate this patient (IM droperidol, IM or IV ketamine, other procedural sedation options, RSI) and all of these have their own risks and benefits (emesis, impact on blood pressure etc.). Then describe how you’d do a chest tube.

Good Luck!

Again, take all the above with a grain of salt. If you find things useful, fantastic. If you prefer to do things another way, that’s great too. The key is really to practice with a number of different people in order to develop your own flow and style.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed, be reassured that if you have the experience and the ability to communicate effectively in the style that StAMPS demands, you’re very likely to do well. It’s just all down to practice from there!

As this site develops, I will try to include more topic-specific practice questions. In the meantime, feel free to reach out to me if you’d like to post an article about a topic of your own!

My email address is [my first name]@[this website].

Leave a Reply